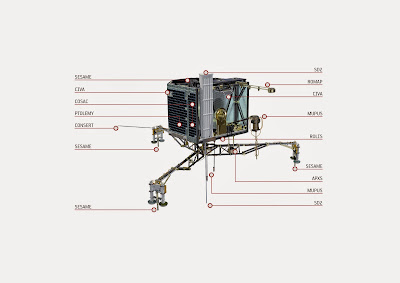

Two examples of dust grains collected by ESA Rosetta's COmetary Secondary Ion Mass Analyser, (COSIMA) instrument in the period 25-31 October 2014.

Both grains were collected at a distance of 10-20 km from the comet nucleus.

Image (a) shows a dust particle (named by the COSIMA team as Eloi) that crumbled into a rubble pile when collected; (b) shows a dust particle that shattered (named Arvid).

For both grains, the image is shown twice under two different grazing illumination conditions: the top image is illuminated from the right, the bottom image from the left.

The brightness is adjusted to emphasise the shadows, in order to determine the height of the dust grain. Eloi therefore reaches about 0.1 mm above the target plate; Arvid about 0.06 mm.

The two small grains at the far right of image (b) are not part of the shattered cluster. The fact that the grains broke apart so easily means their individual parts are not well glued together.

If they contained ice they would not shatter; instead, the icy component would evaporate off the grain shortly after touching the collecting plate, leaving voids in what remained.

By comparison, if a pure water-ice grain had struck the detector, then only a dark patch would have been seen.

These 'fluffy' grains are thought to originate from the dusty layer built up on the comet's surface since its last close approach to the Sun, and will soon be lost into the coma.

Image courtesy ESA /Rosetta et al

ESA's Rosetta mission is providing unique insight into the life cycle of a comet's dusty surface, watching 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko as it sheds the dusty coat it has accumulated over the past four years.

The COmetary Secondary Ion Mass Analyser, (COSIMA), is one of Rosetta's three dust analysis experiments. It started collecting, imaging and measuring the composition of dust particles shortly after the spacecraft arrived at the comet in August 2014.

Results from the first analysis of its data are reported in the journal Nature. "Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko sheds dust coat accumulated over the past four years" - Rita Schulz et al. Nature (2015) doi:10.1038/nature14159

The study covers August to October, when the comet moved along its orbit between about 535 million kilometres to 450 million kilometres from the Sun. Rosetta spent the most of this time orbiting the comet at distances of 30 km or less.

The scientists looked at the way that many large dust grains broke apart when they were collected on the instrument's target plate, typically at low speeds of 1-10 m/s.

The grains, which were originally at least 0.05 mm across, fragmented or shattered upon collection.

The fact that they broke apart so easily means that the individual parts were not well bound together. Moreover, if they had contained ice, they would not have shattered.

Instead, the icy component would have evaporated off the grain shortly after touching the collecting plate, leaving voids in what remained.

By comparison, if a pure water-ice grain had struck the detector, then only a dark patch would have been seen.

The dust particles were found to be rich in sodium, sharing the characteristics of 'interplanetary dust particles'.

These are found in meteor streams originating from comets, including the annual Perseids from Comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle and the Leonids from 55P/Tempel-Tuttle.

"We found that the dust particles released first when the comet started to become active again are 'fluffy'.

They don't contain ice, but they do contain a lot of sodium. We have found the parent material of interplanetary dust particles," says lead author Rita Schulz of ESA's Scientific Support Office.

The scientists believe that the grains detected were stranded on the comet's surface after its last perihelion passage, when the flow of gas away from the surface had subsided and was no longer sufficient to lift dust grains from the surface.

While the dust was confined to the surface, the gas continued evaporating at a very low level, coming from ever deeper below the surface during the years that the comet travelled furthest from the Sun.

Effectively, the comet nucleus was 'drying out' on the surface and just below it.

"We believe that these 'fluffy' grains collected by Rosetta originated from the dusty layer built up on the comet's surface since its last close approach to the Sun," explains Martin Hilchenbach, COSIMA principal investigator at the Max-Planck Institute for Solar System research in Germany.

"This layer is being removed as the activity of the comet is increasing again. We see this layer being removed, and we expect it to evolve into a more ice-rich phase in the coming months."

The comet is on a 6.5-year circuit around the Sun, and is moving towards its closest approach in August of this year.

At that point, Rosetta and the comet will be 186 million kilometres from the Sun, between the orbits of Earth and Mars.

As the comet warms, the outflow of gases is increasing and the grains making up the dry surface layers are being lifted into the inner atmosphere, or coma.

Eventually, the incoming solar energy will be high enough to remove all of this old dust, leaving fresher material exposed at the surface.

"In fact, much of the comet's dust mantle should actually be lost by now, and we will soon be looking at grains with very different properties," says Rita.

"Rosetta's dust observations close to the comet nucleus are crucial in helping us to link together what is happening at the very small scale with what we see at much larger scales, as dust is lost into the comet's coma and tail," says Matt Taylor, ESA's Rosetta project scientist.

"For these observations, it really is a case of "watch this space" as we continue to watch in real time how the comet evolves as it approaches the Sun along its orbit over the coming months."

Both grains were collected at a distance of 10-20 km from the comet nucleus.

Image (a) shows a dust particle (named by the COSIMA team as Eloi) that crumbled into a rubble pile when collected; (b) shows a dust particle that shattered (named Arvid).

For both grains, the image is shown twice under two different grazing illumination conditions: the top image is illuminated from the right, the bottom image from the left.

The brightness is adjusted to emphasise the shadows, in order to determine the height of the dust grain. Eloi therefore reaches about 0.1 mm above the target plate; Arvid about 0.06 mm.

The two small grains at the far right of image (b) are not part of the shattered cluster. The fact that the grains broke apart so easily means their individual parts are not well glued together.

If they contained ice they would not shatter; instead, the icy component would evaporate off the grain shortly after touching the collecting plate, leaving voids in what remained.

By comparison, if a pure water-ice grain had struck the detector, then only a dark patch would have been seen.

These 'fluffy' grains are thought to originate from the dusty layer built up on the comet's surface since its last close approach to the Sun, and will soon be lost into the coma.

Image courtesy ESA /Rosetta et al

ESA's Rosetta mission is providing unique insight into the life cycle of a comet's dusty surface, watching 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko as it sheds the dusty coat it has accumulated over the past four years.

The COmetary Secondary Ion Mass Analyser, (COSIMA), is one of Rosetta's three dust analysis experiments. It started collecting, imaging and measuring the composition of dust particles shortly after the spacecraft arrived at the comet in August 2014.

Results from the first analysis of its data are reported in the journal Nature. "Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko sheds dust coat accumulated over the past four years" - Rita Schulz et al. Nature (2015) doi:10.1038/nature14159

The study covers August to October, when the comet moved along its orbit between about 535 million kilometres to 450 million kilometres from the Sun. Rosetta spent the most of this time orbiting the comet at distances of 30 km or less.

The scientists looked at the way that many large dust grains broke apart when they were collected on the instrument's target plate, typically at low speeds of 1-10 m/s.

The grains, which were originally at least 0.05 mm across, fragmented or shattered upon collection.

The fact that they broke apart so easily means that the individual parts were not well bound together. Moreover, if they had contained ice, they would not have shattered.

Instead, the icy component would have evaporated off the grain shortly after touching the collecting plate, leaving voids in what remained.

By comparison, if a pure water-ice grain had struck the detector, then only a dark patch would have been seen.

The dust particles were found to be rich in sodium, sharing the characteristics of 'interplanetary dust particles'.

These are found in meteor streams originating from comets, including the annual Perseids from Comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle and the Leonids from 55P/Tempel-Tuttle.

"We found that the dust particles released first when the comet started to become active again are 'fluffy'.

They don't contain ice, but they do contain a lot of sodium. We have found the parent material of interplanetary dust particles," says lead author Rita Schulz of ESA's Scientific Support Office.

The scientists believe that the grains detected were stranded on the comet's surface after its last perihelion passage, when the flow of gas away from the surface had subsided and was no longer sufficient to lift dust grains from the surface.

While the dust was confined to the surface, the gas continued evaporating at a very low level, coming from ever deeper below the surface during the years that the comet travelled furthest from the Sun.

Effectively, the comet nucleus was 'drying out' on the surface and just below it.

"We believe that these 'fluffy' grains collected by Rosetta originated from the dusty layer built up on the comet's surface since its last close approach to the Sun," explains Martin Hilchenbach, COSIMA principal investigator at the Max-Planck Institute for Solar System research in Germany.

"This layer is being removed as the activity of the comet is increasing again. We see this layer being removed, and we expect it to evolve into a more ice-rich phase in the coming months."

The comet is on a 6.5-year circuit around the Sun, and is moving towards its closest approach in August of this year.

At that point, Rosetta and the comet will be 186 million kilometres from the Sun, between the orbits of Earth and Mars.

As the comet warms, the outflow of gases is increasing and the grains making up the dry surface layers are being lifted into the inner atmosphere, or coma.

Eventually, the incoming solar energy will be high enough to remove all of this old dust, leaving fresher material exposed at the surface.

"In fact, much of the comet's dust mantle should actually be lost by now, and we will soon be looking at grains with very different properties," says Rita.

"Rosetta's dust observations close to the comet nucleus are crucial in helping us to link together what is happening at the very small scale with what we see at much larger scales, as dust is lost into the comet's coma and tail," says Matt Taylor, ESA's Rosetta project scientist.

"For these observations, it really is a case of "watch this space" as we continue to watch in real time how the comet evolves as it approaches the Sun along its orbit over the coming months."