Radar images from NASA's Cassini spacecraft reveal some new curiosities on the surface of Saturn's mysterious moon Titan, including a nearly circular feature that resembles a giant hot cross bun and shorelines of ancient seas.

The results were presented today at the American Astronomical Society's Division of Planetary Sciences conference in Reno, Nev.

Steam from baking often causes the top of bread to lift and crack. Scientists think some similar process involving heat may be at play on Titan.

The image showing the bun-like mound was obtained on May 22, 2012, by Cassini's radar instrument.

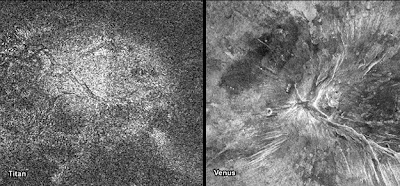

Scientists have seen similar terrain on Venus, where a dome-shaped region about 20 miles (30 kilometers) across has been seen at the summit of a large volcano called Kunapipi Mons.

They theorise that the Titan cross, which is about 40 miles (70 kilometers) long, is also the result of fractures caused by uplift from below, possibly the result of rising magma.

"The 'hot cross bun' is a type of feature we have not seen before on Titan, showing that Titan keeps surprising us even after eight years of observations from Cassini," said Rosaly Lopes, a Cassini radar team scientist based at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

"The 'bun' may be the result of what is known on Earth as a laccolith, an intrusion formed by magma pushing up from below. The Henry Mountains of Utah are well-known examples of this geologic phenomenon."

Another group of Cassini scientists, led by Ellen Stofan, who is based at Proxemy Research, Rectortown, Va., has been scrutinizing radar images of Titan's southern hemisphere.

Titan is the only place other than Earth that has stable liquid on its surface, though the liquids on Titan are hydrocarbon rather than water. So far, vast seas have only been seen in Titan's northern hemisphere.

A new analysis of Cassini images collected from 2008 to 2011 suggests there were once vast, shallow seas at Titan's south pole as well. Stofan and colleagues have found two good candidates for dry or mostly dry seas.

One of these dry seas appears to be about 300 by 170 miles (475 by 280 kilometers) across, and perhaps a few hundred feet (meters) deep.

Ontario Lacus, the largest current lake in the south, sits inside of the dry shorelines, like a shrunken version of a once-mighty sea.

The results were presented today at the American Astronomical Society's Division of Planetary Sciences conference in Reno, Nev.

Steam from baking often causes the top of bread to lift and crack. Scientists think some similar process involving heat may be at play on Titan.

The image showing the bun-like mound was obtained on May 22, 2012, by Cassini's radar instrument.

Scientists have seen similar terrain on Venus, where a dome-shaped region about 20 miles (30 kilometers) across has been seen at the summit of a large volcano called Kunapipi Mons.

They theorise that the Titan cross, which is about 40 miles (70 kilometers) long, is also the result of fractures caused by uplift from below, possibly the result of rising magma.

"The 'hot cross bun' is a type of feature we have not seen before on Titan, showing that Titan keeps surprising us even after eight years of observations from Cassini," said Rosaly Lopes, a Cassini radar team scientist based at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

"The 'bun' may be the result of what is known on Earth as a laccolith, an intrusion formed by magma pushing up from below. The Henry Mountains of Utah are well-known examples of this geologic phenomenon."

Another group of Cassini scientists, led by Ellen Stofan, who is based at Proxemy Research, Rectortown, Va., has been scrutinizing radar images of Titan's southern hemisphere.

Titan is the only place other than Earth that has stable liquid on its surface, though the liquids on Titan are hydrocarbon rather than water. So far, vast seas have only been seen in Titan's northern hemisphere.

A new analysis of Cassini images collected from 2008 to 2011 suggests there were once vast, shallow seas at Titan's south pole as well. Stofan and colleagues have found two good candidates for dry or mostly dry seas.

One of these dry seas appears to be about 300 by 170 miles (475 by 280 kilometers) across, and perhaps a few hundred feet (meters) deep.

Ontario Lacus, the largest current lake in the south, sits inside of the dry shorelines, like a shrunken version of a once-mighty sea.

No comments:

Post a Comment