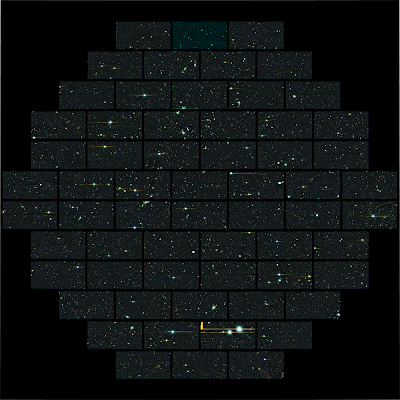

This enormous mosaic of the Milky Way galaxy from NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE), shows dozens of dense clouds, called nebulae.

Many nebulae seen here are places where new stars are forming, creating bubble like structures that can be dozens to hundreds of light-years in size.

Image Credit: NASA

The new Paramount film "Interstellar" imagines a future where astronauts must find a new planet suitable for human life after climate change destroys the Earth's ability to sustain us.

Multiple NASA missions are helping avoid this dystopian future by providing critical data necessary to protect Earth.

Yet the cosmos beckons us to explore farther from home, expanding human presence deeper into the solar system and beyond.

For thousands of years we've wondered if we could find another home among the stars. We're right on the cusp of answering that question.

If you step outside on a very dark night you may be lucky enough to see many of the 2,000 stars visible to the human eye.

They're but a fraction of the billions of stars in our galaxy and the innumerable galaxies surrounding us.

Multiple NASA missions are helping us extend humanity's senses and capture starlight to help us better understand our place in the universe.

Largely visible light telescopes like Hubble show us the ancient light permeating the cosmos, leading to groundbreaking discoveries like the accelerating expansion of the universe.

Through infrared missions like Spitzer, SOFIA and WISE, we've peered deeply through cosmic dust, into stellar nurseries where gases form new stars.

With missions like Chandra, Fermi and NuSTAR, we've detected the death throes of massive stars, which can release enormous energy through supernovas and form the exotic phenomenon of black holes.

Yet it was only in the last few years that we could fully grasp how many other planets there might be beyond our solar system.

Some 64 million miles (104 kilometers) from Earth, the Kepler Space Telescope stared at a small window of the sky for four years.

As planets passed in front of a star in Kepler's line of view, the spacecraft measured the change in brightness.

Kepler was designed to determine the likelihood that other planets orbit stars. Because of the mission, we now know it's possible every star has at least one planet.

Solar systems surround us in our galaxy and are strewn throughout the myriad galaxies we see.

Though we have not yet found a planet exactly like Earth, the implications of the Kepler findings are staggering, there may very well be many worlds much like our own for future generations to explore.

NASA also is developing its next exoplanet mission, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), which will search 200,000 nearby stars for the presence of Earth-size planets.

The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) will discover thousands of exoplanets in orbit around the brightest stars in the sky.

In a two-year survey of the solar neighbourhood, TESS will monitor more than 500,000 stars for temporary drops in brightness caused by planetary transits.

This first-ever spaceborne all-sky transit survey will identify planets ranging from Earth-sized to gas giants, around a wide range of stellar types and orbital distances. No ground-based survey can achieve this feat.

Many nebulae seen here are places where new stars are forming, creating bubble like structures that can be dozens to hundreds of light-years in size.

Image Credit: NASA

The new Paramount film "Interstellar" imagines a future where astronauts must find a new planet suitable for human life after climate change destroys the Earth's ability to sustain us.

Multiple NASA missions are helping avoid this dystopian future by providing critical data necessary to protect Earth.

Yet the cosmos beckons us to explore farther from home, expanding human presence deeper into the solar system and beyond.

For thousands of years we've wondered if we could find another home among the stars. We're right on the cusp of answering that question.

If you step outside on a very dark night you may be lucky enough to see many of the 2,000 stars visible to the human eye.

They're but a fraction of the billions of stars in our galaxy and the innumerable galaxies surrounding us.

Multiple NASA missions are helping us extend humanity's senses and capture starlight to help us better understand our place in the universe.

Largely visible light telescopes like Hubble show us the ancient light permeating the cosmos, leading to groundbreaking discoveries like the accelerating expansion of the universe.

Through infrared missions like Spitzer, SOFIA and WISE, we've peered deeply through cosmic dust, into stellar nurseries where gases form new stars.

With missions like Chandra, Fermi and NuSTAR, we've detected the death throes of massive stars, which can release enormous energy through supernovas and form the exotic phenomenon of black holes.

Yet it was only in the last few years that we could fully grasp how many other planets there might be beyond our solar system.

Some 64 million miles (104 kilometers) from Earth, the Kepler Space Telescope stared at a small window of the sky for four years.

As planets passed in front of a star in Kepler's line of view, the spacecraft measured the change in brightness.

Kepler was designed to determine the likelihood that other planets orbit stars. Because of the mission, we now know it's possible every star has at least one planet.

Solar systems surround us in our galaxy and are strewn throughout the myriad galaxies we see.

Though we have not yet found a planet exactly like Earth, the implications of the Kepler findings are staggering, there may very well be many worlds much like our own for future generations to explore.

NASA also is developing its next exoplanet mission, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), which will search 200,000 nearby stars for the presence of Earth-size planets.

The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) will discover thousands of exoplanets in orbit around the brightest stars in the sky.

In a two-year survey of the solar neighbourhood, TESS will monitor more than 500,000 stars for temporary drops in brightness caused by planetary transits.

This first-ever spaceborne all-sky transit survey will identify planets ranging from Earth-sized to gas giants, around a wide range of stellar types and orbital distances. No ground-based survey can achieve this feat.