When this gas inevitably crashes together, it produces shocks and high-energy gamma-ray photons.

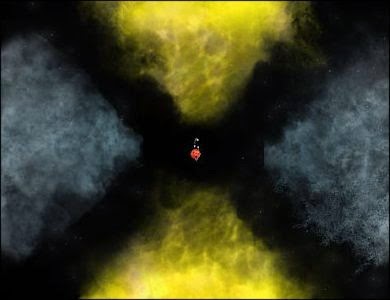

The complex explosion and gas collisions in nova V959 Mon is illustrated here.

In the first days of the nova explosion, dense, relatively slow-moving material is expelled along the binary star system's equator (yellow material in left panel).

The equatorial and polar material crashes together at their intersection, producing shocks and gamma-ray emission (red regions in central panel).

Finally, at later times, the nova stops blowing a wind, and the material drifts off into space, the fireworks finished (right panel).

Credit: Bill Saxton, NRAO/AUI/NSF

Highly-detailed radio-telescope images have pinpointed the locations where a stellar explosion called a nova emitted gamma rays, the most energetic form of electromagnetic waves.

The discovery revealed a probable mechanism for the gamma-ray emissions, which mystified astronomers when first observed in 2012.

"We not only found where the gamma rays came from, but also got a look at a previously-unseen scenario that may be common in other nova explosions," said Laura Chomiuk, of Michigan State University.

A nova occurs when a dense white dwarf star pulls material onto itself from a companion star, triggering a thermonuclear explosion that blows debris into interstellar space.

Astronomers did not expect this scenario to produce high-energy gamma rays.

However, in June of 2012, NASA's Fermi spacecraft detected gamma rays coming from a nova called V959 Mon, some 6500 light-years from Earth.

At the same time, observations with the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) indicated that radio waves coming from the nova probably were caused by subatomic particles moving at nearly the speed of light interacting with magnetic fields.

The high-energy gamma-ray emission, the astronomers noted, also required such fast-moving particles.

Later observations with the extremely-sharp radio "vision" of the Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) and the European VLBI network revealed two distinct knots of radio emission. These knots then were seen to move away from each other.

This observation, along with studies made with e-MERLIN in the UK, and another round of VLA observations in 2014, provided the scientists with information that allowed them to put together a picture of how the radio knots, and the gamma rays, were produced.

In the first stage of this scenario, the white dwarf and its companion give up some of their orbital energy to boost some of the explosion material, making the ejected material move outward faster in the plane of their orbit.

Later, the white dwarf blows off a faster wind of particles moving mostly outward along the poles of the orbital plane.

When the faster-moving polar flow hits the slower-moving material, the shock accelerates particles to the speeds needed to produce the gamma rays, and the knots of radio emission.

"By watching this system over time and seeing how the pattern of radio emission changed, then tracing the movements of the knots, we saw the exact behavior expected from this scenario," Chomiuk said.

Since the 2012 outburst of V959 Mon, Fermi has detected gamma rays from three additional nova explosions.

"This mechanism may be common to such systems. The reason the gamma rays were first seen in V959 Mon is because it's close," Chomiuk said.

Because the type of ejection seen in V959 Mon also is seen in other binary-star systems, the new insights may help astronomers understand how those systems develop.

This "common envelope" phase occurs in all close binary stars, and is poorly understood.

"We may be able to use novae as a 'testbed' for improving our understanding of this critical stage of binary evolution," Chomiuk said.

Chomiuk worked with an international team of astronomers. The researchers reported their findings in the scientific journal Nature.

More information: Binary orbits as the driver of gamma-ray emission and mass ejection in classical novae , Nature, DOI: 10.1038/nature13773