The Cassini spacecraft captures a rare family photo of three of Saturn's moons that couldn't be more different from each other!

As the largest of the three, Tethys (image center) is round and has a variety of terrains across its surface.

Meanwhile, Hyperion (to the upper-left of Tethys) is the "wild one" with a chaotic spin and Prometheus (lower-left) is a tiny moon that busies itself sculpting the F ring.

To learn more about the surface of Tethys (660 miles, or 1,062 kilometers across), see PIA17164.

More on the chaotic spin of Hyperion (168 miles, or 270 kilometers across) can be found at PIA07683, and discover more about the role of Prometheus (53 miles, or 86 kilometers across) in shaping the F ring in PIA12786.

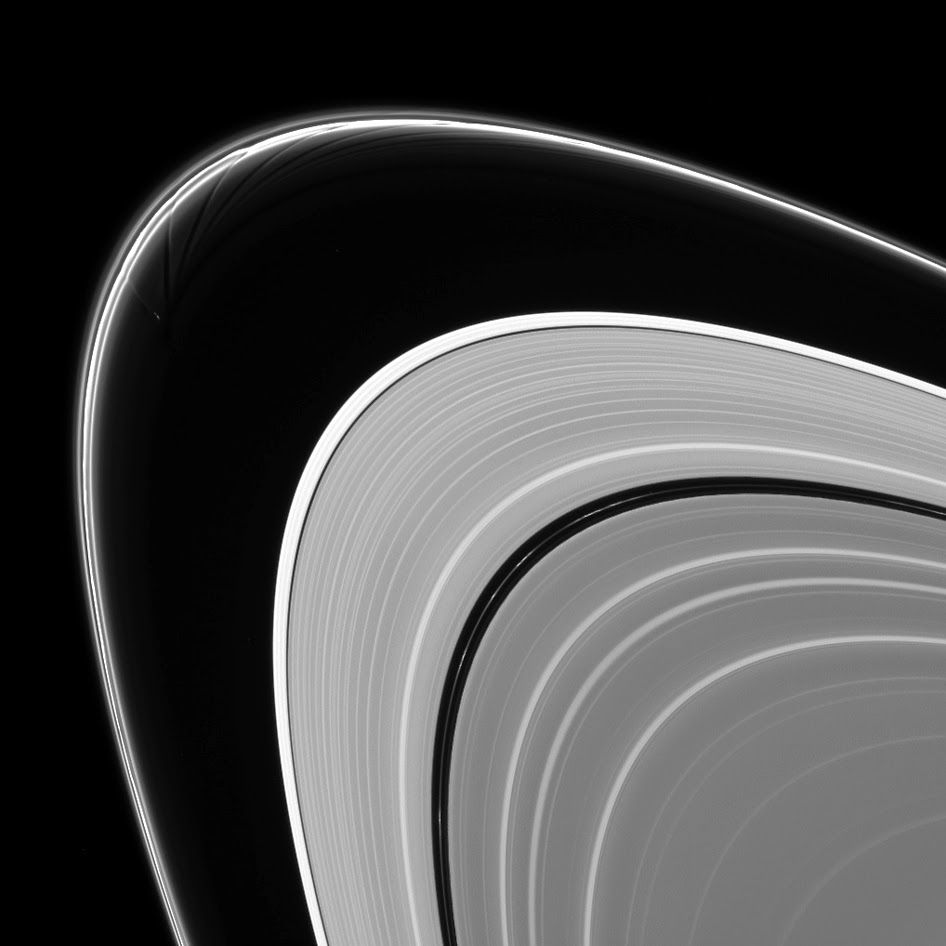

This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 1 degree above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on July 14, 2014.

The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 1.2 million miles (1.9 million kilometers) from Tethys and at a Sun-Tethys-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 22 degrees.

Image scale is 7 miles (11 kilometers) per pixel.

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency.

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington, D.C.

The Cassini orbiter and its two onboard cameras were designed, developed and assembled at JPL.

The imaging operations center is based at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colo.

As the largest of the three, Tethys (image center) is round and has a variety of terrains across its surface.

Meanwhile, Hyperion (to the upper-left of Tethys) is the "wild one" with a chaotic spin and Prometheus (lower-left) is a tiny moon that busies itself sculpting the F ring.

To learn more about the surface of Tethys (660 miles, or 1,062 kilometers across), see PIA17164.

More on the chaotic spin of Hyperion (168 miles, or 270 kilometers across) can be found at PIA07683, and discover more about the role of Prometheus (53 miles, or 86 kilometers across) in shaping the F ring in PIA12786.

This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 1 degree above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on July 14, 2014.

The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 1.2 million miles (1.9 million kilometers) from Tethys and at a Sun-Tethys-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 22 degrees.

Image scale is 7 miles (11 kilometers) per pixel.

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency.

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington, D.C.

The Cassini orbiter and its two onboard cameras were designed, developed and assembled at JPL.

The imaging operations center is based at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colo.