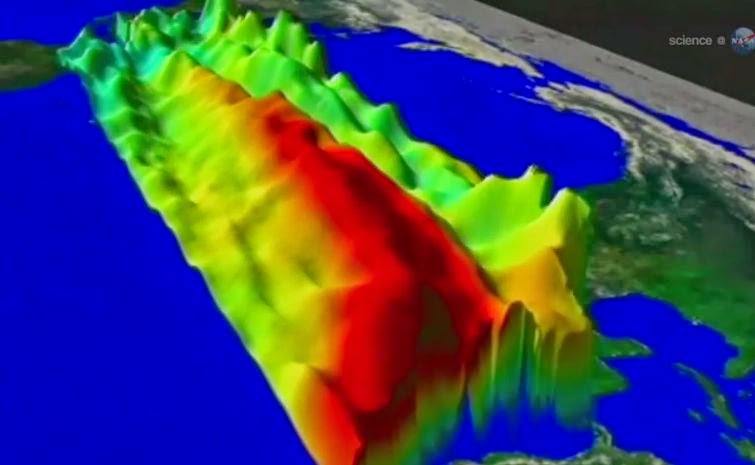

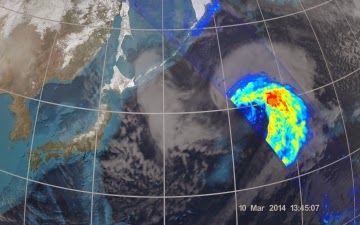

The image shows Kelvin waves of high sea level (red/yellow) crossing the Pacific Ocean at the equator.

The waves can be related to El Niño events. Green indicates normal sea level, and blue/purple areas are lower than normal.

Data are from the NASA /European Jason-2 satellite, collected Sept. 13-22, 2014.

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Prospects have been fading for an El Niño event in 2014, but now there's a glimmer of hope for a very modest comeback.

Scientists warn that unless these developing weak-to-modest El Niño conditions strengthen, the drought-stricken American West shouldn't expect any relief.

The latest sea-level-height data from the NASA /European Ocean Surface Topography Mission (OSTM) /Jason-2 satellite mission show a pair of eastward-moving waves of higher sea level, known as Kelvin waves, in the Pacific Ocean, the third such pair of waves this year.

Now crossing the central and eastern equatorial Pacific, these warm waves appear as the large area of higher-than-normal sea surface heights (warmer-than-normal ocean temperatures) hugging the equator between 120 degrees west and the International Dateline.

The Kelvin waves are traveling eastward and should arrive off Ecuador in late September and early October.

A series of larger atmospheric "west wind bursts" from February through May 2014 triggered an earlier series of Kelvin waves that raised hopes of a significant El Niño event.

Just as the warming of the eastern equatorial Pacific by these waves dissipated, damping expectations for an El Niño this year, these latest Kelvin waves have appeared, resuscitating hopes for a late arrival of the event.

For an overview of 2014's El Niño prospects and Kelvin waves, please see: phys.org/news/2014-05-el-nino.html

This latest image highlights the processes that occur on time scales of more than a year but usually less than 10 years, such as El Niño and La Niña.

The image also highlights faster ocean processes such as Kelvin waves. As Patzert says, "Jason-2 is a fantastic Kelvin wave counter."

These processes are known as the interannual ocean signal. To show that signal, scientists refined data for this image by removing trends over the past 21 years, seasonal variations and time-averaged signals of large-scale ocean circulation.

For a more detailed explanation of what this type of image means, visit: sealevel.jpl.nasa.gov/science/… lninopdo/latestdata/

For a time sequence of the evolution of the 2014 El Nino, visit: sealevel.jpl.nasa.gov/science/… /latestdata/archive/

The waves can be related to El Niño events. Green indicates normal sea level, and blue/purple areas are lower than normal.

Data are from the NASA /European Jason-2 satellite, collected Sept. 13-22, 2014.

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Prospects have been fading for an El Niño event in 2014, but now there's a glimmer of hope for a very modest comeback.

Scientists warn that unless these developing weak-to-modest El Niño conditions strengthen, the drought-stricken American West shouldn't expect any relief.

The latest sea-level-height data from the NASA /European Ocean Surface Topography Mission (OSTM) /Jason-2 satellite mission show a pair of eastward-moving waves of higher sea level, known as Kelvin waves, in the Pacific Ocean, the third such pair of waves this year.

Now crossing the central and eastern equatorial Pacific, these warm waves appear as the large area of higher-than-normal sea surface heights (warmer-than-normal ocean temperatures) hugging the equator between 120 degrees west and the International Dateline.

The Kelvin waves are traveling eastward and should arrive off Ecuador in late September and early October.

A series of larger atmospheric "west wind bursts" from February through May 2014 triggered an earlier series of Kelvin waves that raised hopes of a significant El Niño event.

Just as the warming of the eastern equatorial Pacific by these waves dissipated, damping expectations for an El Niño this year, these latest Kelvin waves have appeared, resuscitating hopes for a late arrival of the event.

For an overview of 2014's El Niño prospects and Kelvin waves, please see: phys.org/news/2014-05-el-nino.html

This latest image highlights the processes that occur on time scales of more than a year but usually less than 10 years, such as El Niño and La Niña.

The image also highlights faster ocean processes such as Kelvin waves. As Patzert says, "Jason-2 is a fantastic Kelvin wave counter."

These processes are known as the interannual ocean signal. To show that signal, scientists refined data for this image by removing trends over the past 21 years, seasonal variations and time-averaged signals of large-scale ocean circulation.

For a more detailed explanation of what this type of image means, visit: sealevel.jpl.nasa.gov/science/… lninopdo/latestdata/

For a time sequence of the evolution of the 2014 El Nino, visit: sealevel.jpl.nasa.gov/science/… /latestdata/archive/