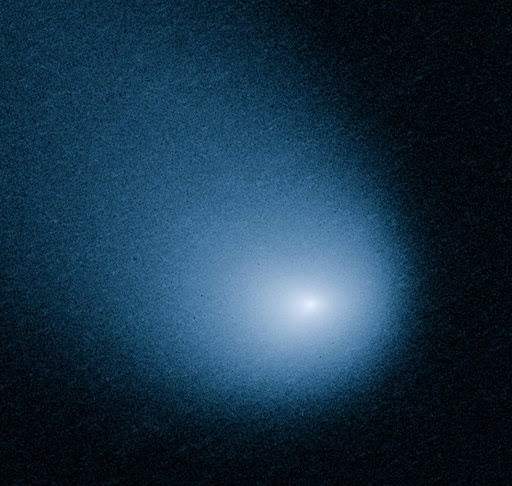

A satellite image showing water-vapour concentration reveals an atmospheric river (yellow) streaming northeast across the Pacific Ocean.

Californians call it the Pineapple Express: a weather pattern that zips across the Pacific Ocean from Hawaii, delivering not baskets of tropical fruit, but buckets of rain and snow.

In meteorological terms, the Pineapple Express is an atmospheric river, a narrow band of air that carries huge amounts of moisture.

For the next six weeks, meteorologists will be plying the eastern Pacific by air and sea, in the hope of catching several atmospheric rivers barrelling towards the coast.

It is the biggest push yet to understand these phenomena, which have received serious scientific attention only in the past decade.

Atmospheric rivers get their start over warm tropical waters; they then flow eastwards and towards the poles a kilometre or two above the ocean surface.

They may stretch for thousands of kilometres, but are only a few hundred kilometres wide. When they hit land, they start to drop their moisture in torrential downpours or blizzards.

“When we have too many atmospheric rivers, floods can occur, and when we don’t have enough we gradually fall into drought,” says Marty Ralph, a meteorologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California, and a leader of the field campaign.

In Europe, atmospheric rivers affect mostly the western part of the continent, but they can be felt as far inland as Poland.

In North America, the entire west coast is affected, and parts of the central and eastern United States occasionally feel the effects of atmospheric rivers that develop over the Gulf of Mexico.

The moisture is often welcome, bringing up to half of the year’s water supply in affected areas1.

A 2013 study found that as many as three-quarters of all droughts in the Pacific Northwest between 1950 and 2010 had been brought to an end by atmospheric-river storms2.

California has been stricken by drought for years (Nature 512, 121–122; 2014), but last month, an atmospheric river dropped enough rain to erase one-third of the water deficit of one major reservoir in just two days.

Climate change may bring stronger and more frequent atmospheric rivers, because the warmer the atmosphere is, the more water it can hold, says David Lavers, a meteorologist at Scripps who is not involved in the project.

“The more you know about how the atmosphere behaves,” he says, “the better position you’re in to prepare for extreme events.”

Read the full article on Nature website - Nature 517, 424–425 (22 January 2015) doi:10.1038/517424a

Californians call it the Pineapple Express: a weather pattern that zips across the Pacific Ocean from Hawaii, delivering not baskets of tropical fruit, but buckets of rain and snow.

In meteorological terms, the Pineapple Express is an atmospheric river, a narrow band of air that carries huge amounts of moisture.

For the next six weeks, meteorologists will be plying the eastern Pacific by air and sea, in the hope of catching several atmospheric rivers barrelling towards the coast.

It is the biggest push yet to understand these phenomena, which have received serious scientific attention only in the past decade.

Atmospheric rivers get their start over warm tropical waters; they then flow eastwards and towards the poles a kilometre or two above the ocean surface.

They may stretch for thousands of kilometres, but are only a few hundred kilometres wide. When they hit land, they start to drop their moisture in torrential downpours or blizzards.

“When we have too many atmospheric rivers, floods can occur, and when we don’t have enough we gradually fall into drought,” says Marty Ralph, a meteorologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California, and a leader of the field campaign.

In Europe, atmospheric rivers affect mostly the western part of the continent, but they can be felt as far inland as Poland.

In North America, the entire west coast is affected, and parts of the central and eastern United States occasionally feel the effects of atmospheric rivers that develop over the Gulf of Mexico.

The moisture is often welcome, bringing up to half of the year’s water supply in affected areas1.

A 2013 study found that as many as three-quarters of all droughts in the Pacific Northwest between 1950 and 2010 had been brought to an end by atmospheric-river storms2.

California has been stricken by drought for years (Nature 512, 121–122; 2014), but last month, an atmospheric river dropped enough rain to erase one-third of the water deficit of one major reservoir in just two days.

Climate change may bring stronger and more frequent atmospheric rivers, because the warmer the atmosphere is, the more water it can hold, says David Lavers, a meteorologist at Scripps who is not involved in the project.

“The more you know about how the atmosphere behaves,” he says, “the better position you’re in to prepare for extreme events.”

Read the full article on Nature website - Nature 517, 424–425 (22 January 2015) doi:10.1038/517424a